Classical Sources

Greek and Roman writers and historians have provided much of the information and ideas we have on the Etruscans today. They theorized on the origins of the Etruscans, told of the Etruscan culture, and gave historical accounts of Etruscan interactions with other nations. Three Greeks spoke of the origins of the Etruscans, though all had different theories.

Hesiod, in the Theogony, said “and Circe the daughter of Helius, Hyperion’s son, loved steadfast Odysseus and bare Agrius and Latinus who was faultless and strong: also she brought forth Telegonus by the will of golden Aphrodite. And they ruled over the famous Tyrsenians, very far off in a recess of the hold islands [1]." According to Hesiod, the children of Odysseus and Circe originated the Etruscan people, a theory not based on historical fact, but rather, stories. Herodotus was the next historian to speak on the Etruscans. He said the Etruscans emmigrated from Lydia due to a famine in their land. The Lydians split their people into two groups. One group was sent to look for a new place to live. This group was the beginning of the Etruscans. Most Greek and Latin historians agreed with this theory until 400 years later, when Dionysius of Halikarnassos refuted it. He believed that the Etruscans were natives to northern Italy. The origins of the Etruscans is still an object of debate for modern historians.

Aristotle spoke of Etruscan robbers to describe his philosophy on souls. He depicted the Etruscan robbers as calloused, saying they “killed with studied cruelty [2]” and “their bodies, the living [corpora viva] with the dead, were bound so exactly as possible one against another [3].” He then compared the harsh robbers to souls: “so our souls, bound together with our bodies, are like the living joined with the dead [4].” Aristotle believed that the soul of a person was punished for grave crimes by the estrangement of happiness. In describing this idea, Aristotle gave historians a picture of a part of Etruscan society.

Livy was a Roman historian that spoke of the Etruscans. He recounted the story of Veii and its first king. The Etruscans were firmly against monarchies, but the Veientines were tired of the election process that occurred every year. The king that was elected ended the festival of the Games, which was particularly detrimental to the Etruscans because religious ceremonies were a fundamental part of their society. Livy also described Etruscan histriones, or dancers. The earlier histriones danced to flute music, though chants were later added with the dances. The music was later broken into different movements. The Etruscan histriones greatly influenced Roman actors and playwrights.

In the Histories, Polybius told the history of the Gallic invasion and Hannibal’s invasion of Etruria. In 225 BC, the Gauls invaded Etruria without any resistance. Etruscan and Sabine troops had not mobilized, but by the time the Gauls moved towards Rome, they were met by the Etruscan and Sabine forces. However, the Gauls crushed the Etruscans and Sabines. The army of Aemilius met the Gauls quickly after the defeat of Etruria and the Gauls were pushed north. Polybius then, in the next book, discussed the invasion of Hannibal. Hannibal passed through Etruria while heading towards Rome. Polybius said Hannibal “continued to burn and devastate the country on his way, with the view of provoking the enemy [5].” When Hannibal saw the Romans, he launched a surprise attack. His army crushed the Roman army. Because of Hannibal’s invasion, Etruria was left in ruin.

These classical primary sources add to the rich history of Etruria. They give accounts of Etruscan affairs while also teaching Etruscan culture in an unparalleled way. The Etruscans can be better understood because of the words of these Greeks and Romans.

[1] Hesiod, Works and Days, Theogony and The Shield of Heracles (New York: Dover Publications, 2006), 55.

[2] Abraham P. Bos, “Aristotle on the Etruscan Robbers: A Core Text of ‘Aristotelian Dualism,’” Journal of the History of Philosophy 41 (July 2003): 292, accessed September 21, 2016, doi:10.1353/hph.2003.0024.

[3] Abraham P. Bos, “Aristotle on the Etruscan Robbers,” 292-293

[4] Abraham P. Bos, “Aristotle on the Etruscan Robbers,” 293

[5] Polybius, The Histories of Polybius (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1922-1927), 203, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Polybius/3*.html.

Remains of Portonaccio Temple at Veii

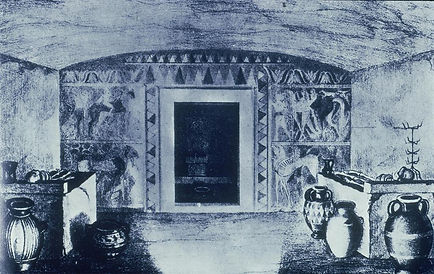

Reconstruction drawing of the interior of Campana Tomb at Veii